At least 18 states require that doctors who know about substance use during pregnancy turn their patients in. A woman could be arrested just for being honest with her doctor

A36-year-old Alabama woman is facing felony charges for filling a doctor’s prescription. Kim Blalock, a mother of six, suffers from severe back pain caused by degeneration of her spinal discs. “There are days that I can’t get up,” Blalock has said. Her condition worsened over the years following surgeries and car accidents. An orthopedist prescribed hydrocodone, an opiate pain killer, and she started using it occasionally when the pain became too much to handle. She stopped taking her prescription during her most recent pregnancy, but as her bump grew, the weight added pressure on her back, and the pain worsened. Midway through her third trimester, she couldn’t take it any more, and refilled her prescription. She gave birth to a healthy baby boy soon after, this past September. Out of caution, she told her doctor about medications she had taken during pregnancy – including the hydrocodone. That’s where the trouble started. After her son tested positive for hydrocodone, an investigation was launched. The state child services agency found no wrongdoing, but the local police and district attorney pressed on. Two months after she gave birth, seven armed officers raided her house, terrifying her children.

Blalock is charged with prescription fraud; prosecutors allege that she committed a crime when she failed to inform her prescribing doctor that she was pregnant before refilling her hydrocodone. It’s a novel charge for such a case, but Alabama has a long history of prosecuting pregnant women under a strict reading of a statute against “chemical endangerment of a child”, which classifies substance use during pregnancy as a form of child abuse. Since 2006, when meth labs were appearing across rural communities, Alabama has made it a felony to expose a child to a chemically toxic environment. The law was meant to enforce heavier penalties on people who make drugs around children, exposing them to the vapors that are emitted in the creation of crack and meth. But prosecutors quickly began deploying the law against pregnant women, interpreting a “chemically toxic environment” to mean the pregnant body itself.

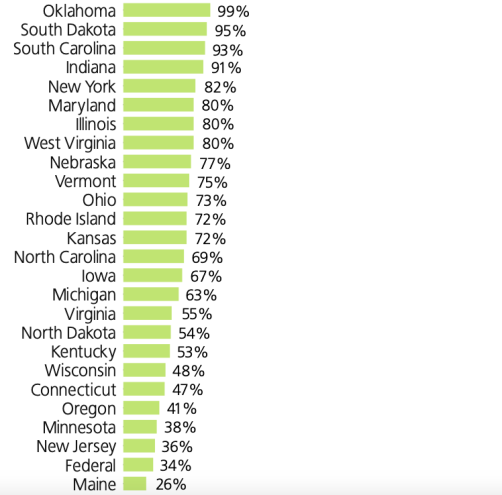

And so, in Alabama, women’s bodies became one of the most hotly contested fronts in the “war on drugs”. But drug laws are being used to criminalize pregnant people throughout the US. Twenty-three states and the District of Columbia have such laws, known as “chemical endangerment of a child” statutes, on the books. Whatever their intent, such laws in practice often enable prosecutors to charge drug use by pregnant women as a felony. Enforcement is not merely a matter of increasing charges and punishments against defendants who happen to be pregnant: at least 18 states legally require that doctors who know about substance use during pregnancy – like Blalock’s obstetrician – turn their patients in. A woman carrying a healthy pregnancy could be turned into the police just for being honest with her own doctor.

Nationwide, the results of such laws have been chilling: California prosecutors charged a woman with murder – via chemical endangerment – after she gave birth to a stillborn infant, claiming that her use of methamphetamine while pregnant was tantamount to homicide. A judge dismissed the charges in May, but did not rule that California’s homicide statutes can’t be used against pregnant women who consume drugs.

But illegal drugs are not the only ones women are being arrested for taking. A shocking number of cases have been brought, both in Alabama and around the country, against women who merely took their medication as prescribed while they happened to be pregnant. After a 2016 investigation found that more than 500 Alabama women had been prosecuted under the state’s chemical endangerment law for filling their prescriptions while pregnant, the state legislature clarified that the law was meant to apply only to recreational drugs, not prescription drugs. Yet Blalock, who merely filled her own prescription, is still being charged for taking her meds. Her prosecution suggests that Alabama authorities are looking for creative ways to limit the rights of pregnant women, regardless of the clearly expressed intent of their own legislature.

For many women, this will be the takeaway: don’t trust the doctor

The case raises troubling questions. Since Blalock is being charged with a felony for not disclosing her pregnancy, does that mean that pregnant people in Alabama have an obligation to share such sensitive information – even when they haven’t been asked? Since prosecutors claim that it was illegal for Blalock to take her meds while pregnant, but was not illegal for her to take them when she wasn’t pregnant, does that suggest that pregnancy negates a patient’s right to medical treatment? Are some conditions worth treating in patients who aren’t pregnant, but somehow not worth treating in patients who are?

And what about the mandatory reporting elements that are included in so many of these statutes – how will this hollowing-out of doctor-patient confidentiality impact health outcomes? It’s hard not to dwell on the realization that if Blalock hadn’t been frank with her doctor, she would have been spared this entire ordeal.

For many women, this will be the takeaway: don’t trust the doctor. When laws incentivize women to be dishonest with their medical providers, or forgo medical care entirely while pregnant, it’s not clear how those laws can be said to ensure the safety of a fetus. If anything, they seem to be discouraging the practices that lead to good pregnancy outcomes.

In the meantime, Blalock is still suffering. “It really has taken its toll,” she said of her felony charge. “I didn’t get to bond with my baby. I’ve had severe postpartum depression with this baby.” If there’s any so-called “child endangerment” in this case, it’s not coming from her.

- Moira Donegan is a Guardian US columnist and the article was published here

You must be logged in to post a comment.